Pest Control

How a little auto parts dealer highlights the systemic risk of a rapidly growing market.

If you find this article interesting, click the like button for me! I would greatly appreciate it :)

You open a business, excited to get your feet off the ground, and you venture out to the bank to get a loan for some equipment. When you arrive, the bank is unwilling to lend you a loan, given that you are a new business with limited collateral to offer. What next? What if you’re a part of a fictional distressed toy manufacturer, Awesome Toys, with a poor credit rating? Are there alternatives to having loans on the books with unfavorable terms and harsh penalties for late payments? Enter private credit.

I’m making it sound bad, but the private credit markets are really foundational to the success of startups and small companies around the country. These institutional asset managers often take equity with venture capital funding or give direct loans. A fictional asset management company, Blackhawk Capital, raises money from a mix of non-bank financial institutions (NBFI) such as insurance companies, pensions, and university endowments, and has promised exceptional returns on the capital locked away for 5-10 years.

Blackhawk Capital decides to take 10% of that money and invest in Awesome Toys, considering the economy is booming, and they will likely be able to pay over the course of 10 years. This transaction has nothing to do with a bank, so it is unregulated, not liquid/locked for 10 years, and the company may not have to report it on a credit filing. What if the toy company was worse than they thought, or the economy was not as strong?

When Awesome Toys goes bankrupt, when does Blackhawk Capital have to mark down their books, how do they pay out their investors, and what if they can’t? Many believe this is the exact situation we find ourselves in now, on the billion-dollar scale. Recently, a Dallas subprime auto lender, Tricolor Holdings, filed for bankruptcy. Tricolor has allegedly committed fraud, providing loans to illegal immigrants, those without licenses, and using the same collateral on multiple loans. This is egregious and just a one-off thing with a bad company, but the billions of losses for asset managers and banks strike some small fears not seen since the 2008 financial crisis.

Soon after, a car parts company, First Brands, also went bankrupt. They were using private credit as a de facto cash buffer, and these shady loans piled up to an unsustainable degree. While the subprime auto market is nowhere near the size of the subprime housing crisis in 2008, it sparked some uneasiness among many big names, including Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase.

And I probably shouldn’t say this, but when you see one cockroach, there are probably more… Everyone should be forewarned on this. - Jamie Dimon

This also raised some questions, even in the mainstream, about the risk of private credit in debt markets. Bank lending is very regulated, while private credit is quite opaque. We can hope that these funds are being diligent with their money, but clearly, bad loans are being made; it’s just a matter of what extent. Some people have found evidence of other sketchy behavior, like layering of funds, which makes the debt even more opaque. A tertiary vehicle owns a company, that owns a company, that owns a company…

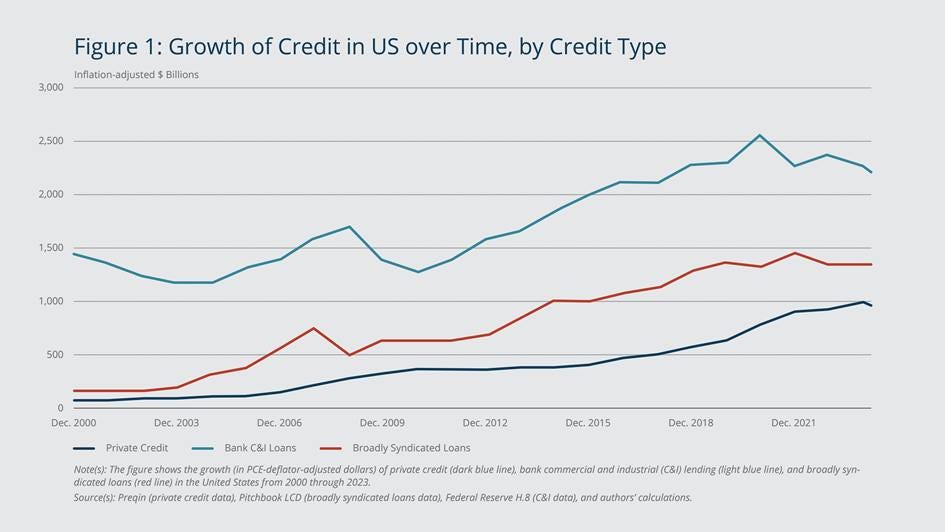

The role of private credit and its impact on financial stability is becoming more important by the year. The market was insignificant in 2000, but is now a large percentage of corporate loans and has surpassed $1 trillion in 2023 (likely close to $2 trillion now). While bank lending and syndicated loans (bank loans to institutions that then trade/make loans) have been decreasing, private credit has been exploding higher.

Banks are often getting involved in roundabout ways, though. Banks may give loans to NBFIs, like a hedge fund or insurance company, which then lends out to private credit funds. The layers go deep, and the model isn’t as simple as the bank lending to the business. NBFIs are sometimes referred to as shadow banks, because it is unclear what is really going on. The main risk is that some of these assets go under, and all of a sudden, there is contagion risk to other entities that hold the debt, or hold the debt of those who did. Even banks could hold some of this risk, even if they are not engaging in the risky lending themselves.

The fact of the matter is that private credit is, in theory, a good thing. Having thriving open capital markets in the world is what allows the US to capture so much investment, innovation, and develop the best companies in the world. Companies may be able to restructure debt or finance in creative ways to become successful. On top of this, the private credit markets are still smaller than other forms of lending, like bank lending, so the risks aren’t insurmountable. This only highlights a potential risk to the system and what could trigger or exacerbate any credit/financial issues in the next recession.

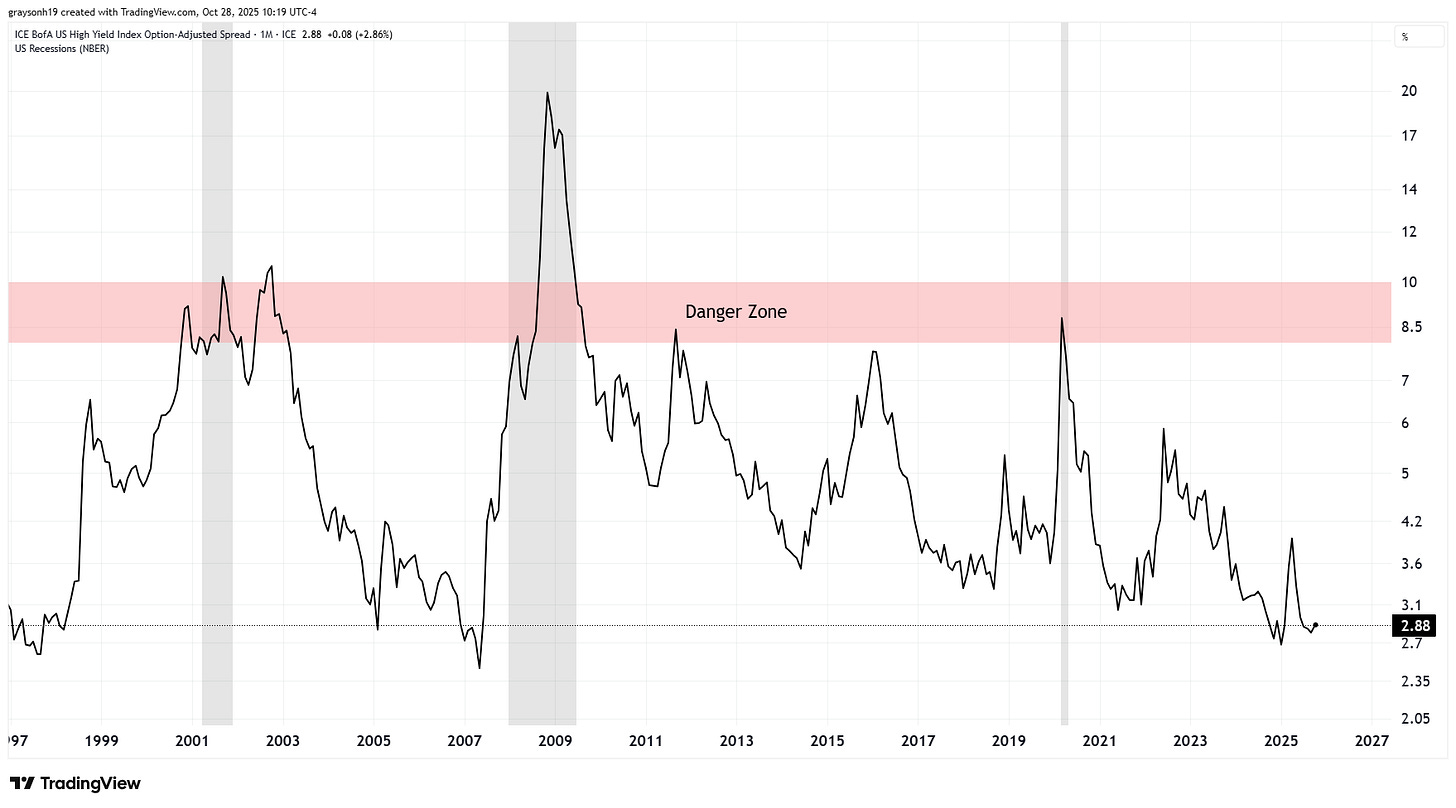

To track the real risk of the credit markets, I look to credit spreads, or the yield on risky/junk bonds compared to safe treasury bonds. There is a higher yield/returns for taking on riskier debt, which blows out during recessions when everyone is scared to own risky debt because many likely are going bankrupt. Now, we are seeing record low spreads between junk and treasuries, implying that there is no risk in credit markets and junk is not very dangerous to hold compared to treasury bonds.

This suggests that credit markets are healthy right now and have a long way to go before we hit the “danger zone” of defaults seen in recessions. However, is junk debt really so safe to only pay 2.8% more than a treasury bond? With cracks in some of these auto lenders, the teetering labor market, and deteriorating consumer, it may seem unlikely.

One potential explanation is from Michael Howell, who suggests the stability has to do with liquidity. Debt-to-GDP has little relation to credit cycles, but liquidity does. Debt and liquidity are connected and dependent, with imbalances leading to a credit crisis or bubble. Since 2015, we have been in an environment of excess liquidity, which is obvious considering the magnitude of Federal Reserve quantitative easing, treasury bill issuance, and federal spending. This has led to the bubble we are in today, seen clearly in stocks, crypto, and housing. His work suggests liquidity will be leaving the financial system soon, resulting in refinancing tensions and potential credit issues.

There are similarities and differences between 2008. We have another housing bubble, this time stocks along with it, but the subprime mortgages are not an issue. We do have auto lenders going bankrupt, but that is hardly a contagion risk with its relatively smaller size. With banks left with harsher regulations after 2008, bank lending has not been the same. Now, the new guy in town is private credit, rapidly growing to over $1 trillion and taking market share from direct bank lending in recent years.

I’m not suggesting these auto lenders are the straw that breaks the camel’s back; this is highlighting a potential black swan event in the credit markets. The US regulators don’t have a good idea what is going on with shadow loans and private lenders. When liquidity continues to tighten over the coming year, there will be more cockroaches out there. We now have two examples in the auto lending industry. What else is hiding under the surface? Until next week,

-Grayson

Socials

Twitter/X - @graysonhoteling

Archive - The Gray Area

Notes - The Gray Area

Promotions

Sign up for TradingView