Not So Bright Pt. 2

The sun does what? Another unloved sector is poised for disruption.

If you find this article interesting, click the like button for me! I would greatly appreciate it :)

To start the year, I released an article called Not So Bright, an unconventional piece. In it, I discussed how solar cycles and “space weather” have an uncanny correlation with the economic business cycle, stock market volatility, and major global events. The science behind geomagnetic storms (a greater chance at solar maximum) affecting human health and behavior is beautiful. The connection to global events is admittedly far from proven, but the heavy correlations and potential causation are certainly there.

In short, a solar maximum is characterized by increased solar magnetic activity. This manifests in greater sunspot numbers, more solar flares and geomagnetic storms (auroras), more radiation and particle bombardment from the sun. While a maximum this can pose a risk to electronic infrastructure, a solar minimum can pose challenges for other reasons.

While we get less bombardment from the sun, the sun deflects galactic cosmic rays entering the solar system. Solar minimum does not modulate these rays as much, meaning more particles hit Earth, despite those increased risks from our own star spitting out particles and radiation.

Long story short, the solar cycle has an impact on temperature, which is substantiated by scientific literature. While I’m not here to argue the merits of climate change and carbon dioxide forcing (that gets you in trouble these days), I’m merely pointing out the effects that the solar cycles do have (the extent to which climatological forces dominate is debated and not my purpose). There is a cooling effect at sunspot minimums, but the mechanism is more complicated than it seems.

[Science] There is less visible and infrared radiation during solar minimum, which reduces the total solar irradiance, but this effect is surprisingly small. Less ultraviolet light means less effect on stratospheric ozone, which has coupling effects with oceans, wind, and surface temperature. Finally, the atmosphere is a big electric circuit, meaning changes in charged particles can impact things like storms (why unusual weather follows geomagnetic storms, like the polar vortex recently). During solar minimum, the increase in cosmic rays or galactic charged particles hitting Earth and attracting water vapor, which contributes to cloud seeding. Greater cloud cover increases solar reflectivity, and less solar radiation reaches the surface, thus causing a cooling effect.

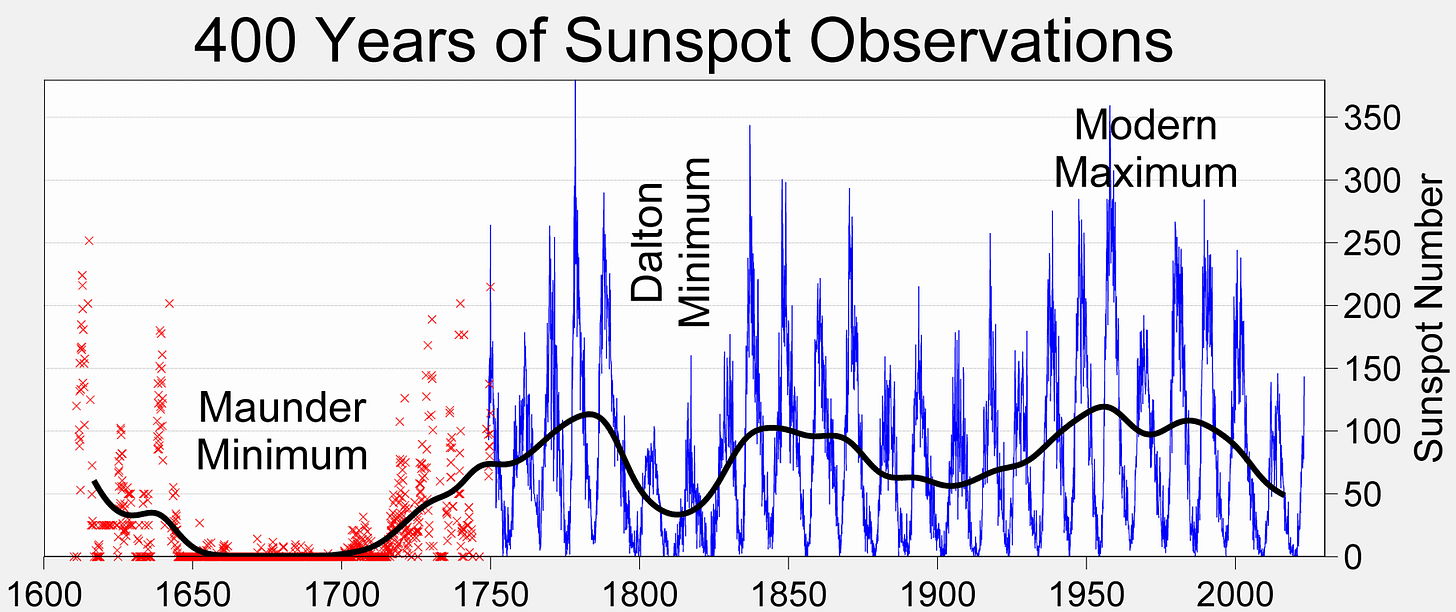

Right now, you are probably thinking that these solar cycles occur every 11 years and global temperatures have been rising steadily for the last 55 years, so what is the point? It turns out we have to think larger than our own lives. The sun, in its magnificence, undergoes magnetic cycles on a timescale longer than just 11 years. These cycles just track the intensity of groups of 11-year cycles.

Schwabe cycle ~11 years

Gleissberg Cycle ~100 years

Suess-DeVries Cycle ~200 years

Hallstatt Cycle ~2400 years

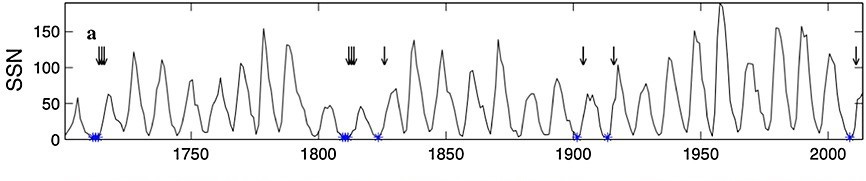

Solar activity can be traced through tree rings, ice cores, and isotope data. The Suess-DeVries Cycle minimums correlate to the Maunder minimum from 1650-1710 and great depression era around 1900-1930. The Gleissberg cycle lines up with the Dalton minimum, great depression era, and we should be entering one now.

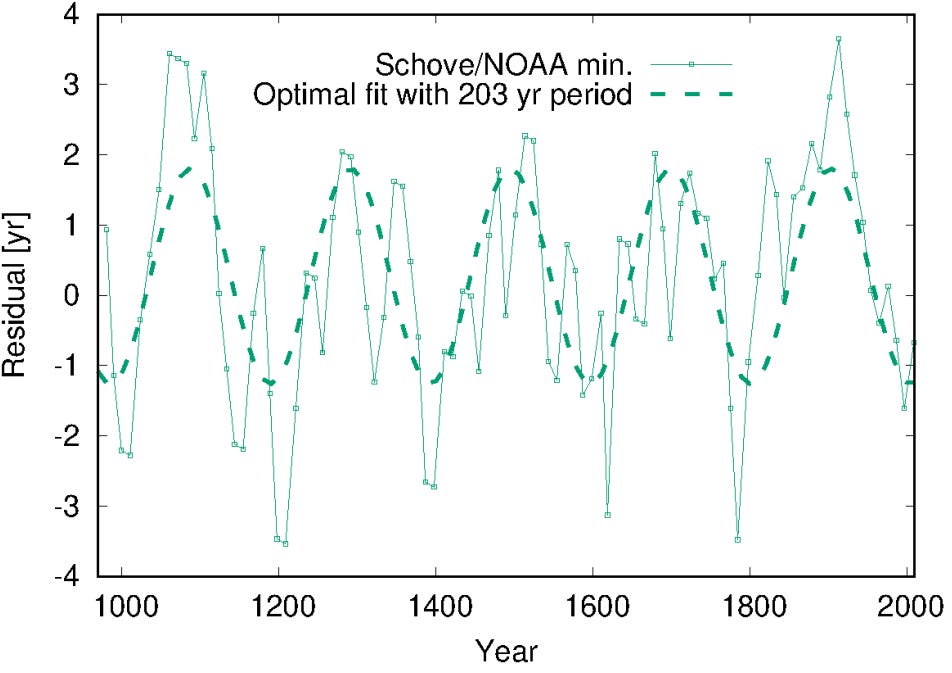

The 200-year Suess-DeVries Cycle is statistically significant, as shown by the paper below. The peaks in the figure below track with the Suess-DeVries Cycle minimums and go back 1000 years of data. We are currently at a high in this cycle.

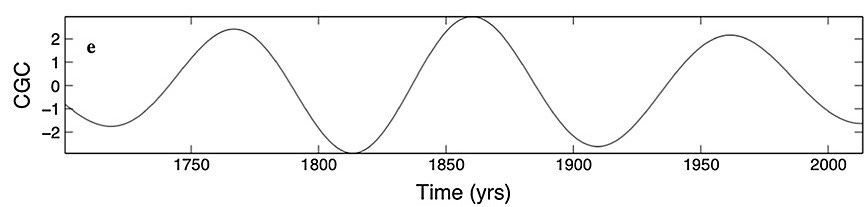

The ~100-year Gleissberg Cycle is also shown to be significant. Past minimums correspond to the early 1900s, early 1800s, and early 1700s. While we are at maximum in the Suess-DeVries cycle, we are at a minimum in the Gleissberg Cycle.

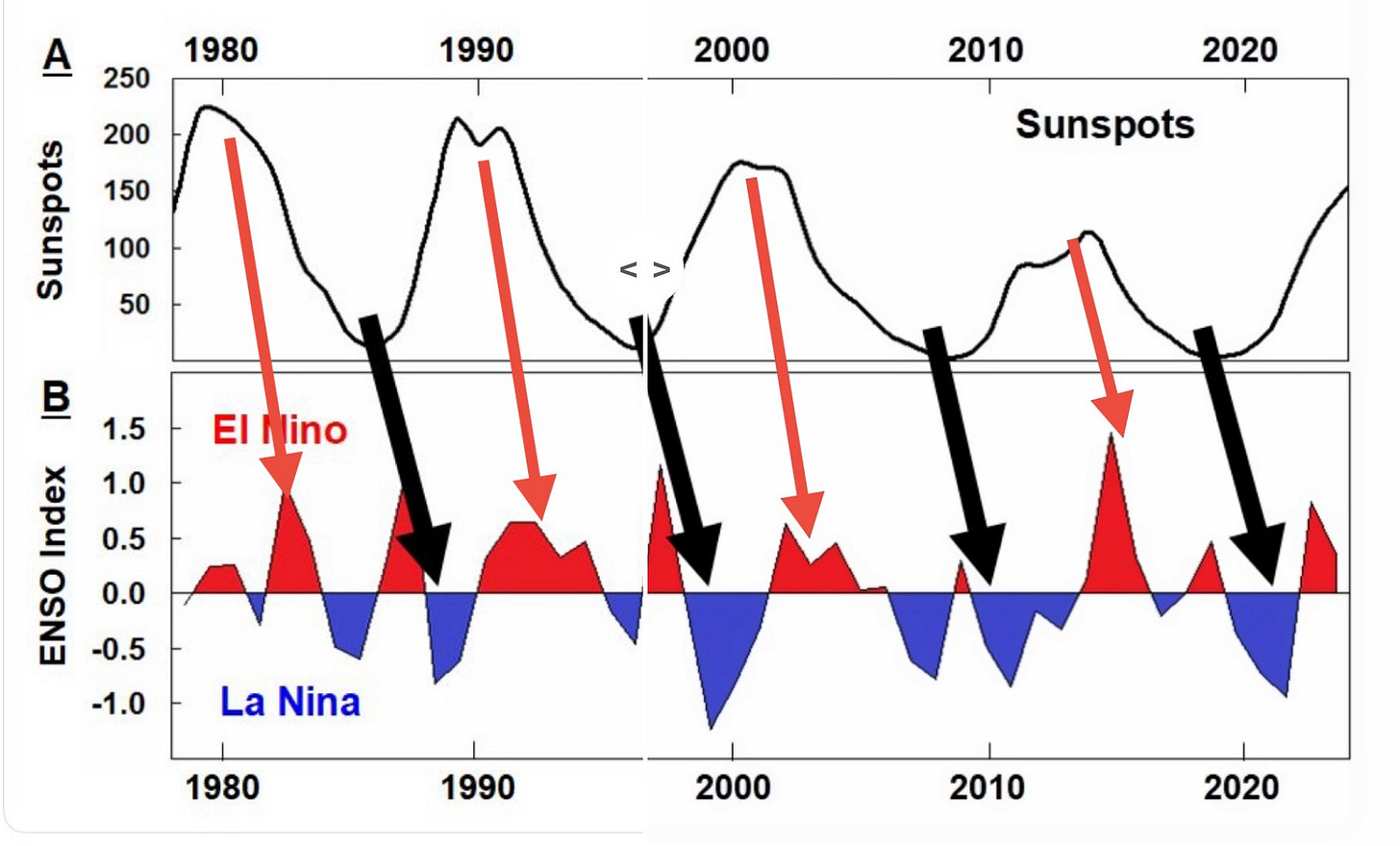

We know that solar forcing has an impact on ocean temperatures and wind patterns, so it shouldn’t be a surprise that the ENSO events (El Niño, La Niña) correlate with solar cycles. Typically, following a solar maximum, there is a 1-4 year lag to El Niño and a subsequent lag from minimum to La Niña.

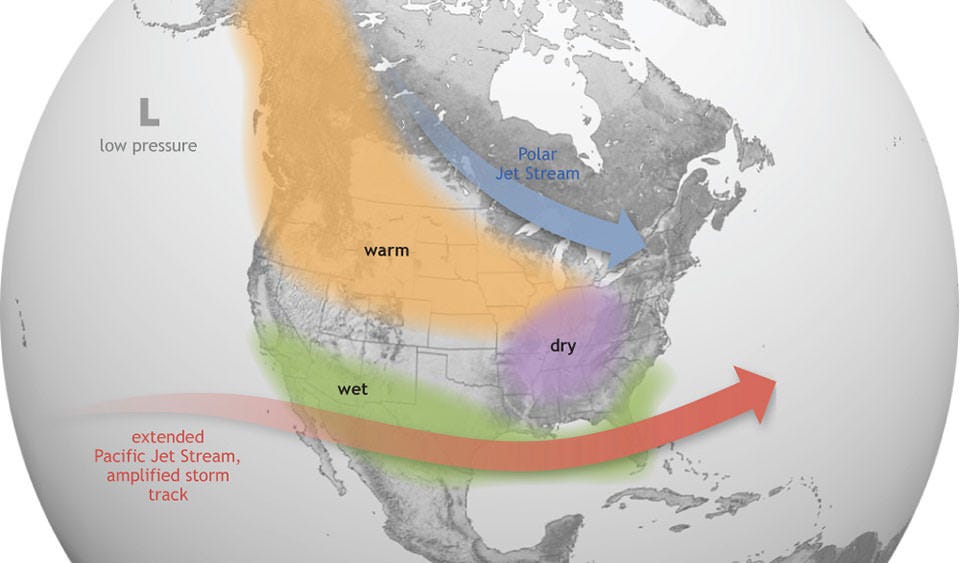

El Niño typically brings wetter conditions to the southern US, with warmer, drier conditions to the north and middle. La Niña is typically the opposite, yielding drier conditions in the south and colder/wetter conditions in the middle/north.

It should be clear why these cycles may matter. If the small solar cycles have a significant impact on weather, then the long ones should too. The weather affects one of the most important things: agriculture. While more important during agrarian societies without industrial fertilizers, it is still vital today and has effects on the US in recent cycles too.

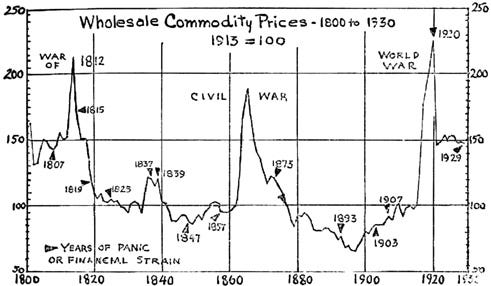

The Dalton minimum of the early 1800s brought colder conditions and agricultural hardship to North America. This period is famous for 1816, the “year without a summer.” There were widespread crop failures, food shortages, and commodity price spikes.

Most of you are likely more familiar with the last Gleissburg minimum, the Great Depression era. World War I and the economic depression brought significant volatility in commodity prices. The Dust Bowl was a core issue exacerbating economic hardship during this time. Widespread crop failures and agricultural displacement took place during this time period.

We are at the next Gleissburg minimum now. This is further evidence to suggest volatile commodity prices. With modern technology, food systems, and a non-agrarian economy, we thankfully may be more insulated from its effects. On the flip side, we may be less resilient to its effects and not expect it.

The Midwest is the breadbasket of the world, and a significant centralization of our food supply has already occurred. It may not be unreasonable to suspect a second Dust Bowl or agrarian issues due to colder, not hotter, than expected temperatures.

Gold, silver, uranium, and industrial metals have seen incredible volatility over the last year. Wheat and agricultural commodities, while experiencing volatility in 2022, have not joined this move. We are a technology-driven world, not bothered by boring real-world sectors of the economy like energy or commodities. A boring sector like agriculture may gain a greater share of importance and investment if weather/economic challenges do take place. Until next week,

-Grayson

Socials

Twitter/X - @graysonhoteling

Archive - The Gray Area

Notes - The Gray Area

Promotions

Sign up for TradingView