🔋Eight Deadly Sins Debunked

Are renewables a breakthrough technology primed for dominance, or an energy source facing more challenges than meet the eye?

Better Batteries turned The Gray Area - for more info on why, see here. Thanks for reading! Enjoy and don’t forget to leave a like on the post!

Welcome to the same newsletter, but with a different name! A few weeks ago I published a piece called That’s So Metal, a part two of the discussion of energy return on energy invested (EROEI) which I outline why metals will drift higher in price in a squigly path on the basis of the resource intensity of wind/solar/batteries and projected demand. I cannot account for every single factor that goes into these complex topics for each article to keep them brief and for my own time. One additional point was the debt and currency debasement which will also drive hard asset prices like metals higher in the future. I have made arguments why this is inevidable before. This article sparked some discussion in the comments and rightfully people pointed to technological changes moving swiftly, unpredictably, and resourcefully as possible rebuttles. I was pointed to an article from Renewable Revolution called The Eight Deadly Sins of Analyzing the Energy Transition which discusses a lot of the blind spots where people underestimate the energy transition in progress with the implication that I’m commiting one or some of these sins.

The authors of this Substack are a part of the Rocky Mountain Institute, a very pro renewables energy transition firm which I would say agree with the mainstream energy transition narrative. The narrative is really ideology with a swath of society, and can be broadly described as aggressively pro-wind/solar/EVs, anti-nuclear, and very anti-fossil fuel. I highly encourage you to read the article before this one if you have time and draw your own thoughts, but I’ve summarized each section in my words before each section for your convenience.

Of course it’s a fools errand debating ideology with logic, but I thought I’d point out a few things the article misses and maybe some I agree with this week and draft my own list of sins which will come out next week. Enough is enough, time to play the jester, let’s go.

Italicized text is my summary from the article of discussion.

1. Linear thinking

Technological change is exponential (S-surve) and wind/solar/batteries will follow this path.

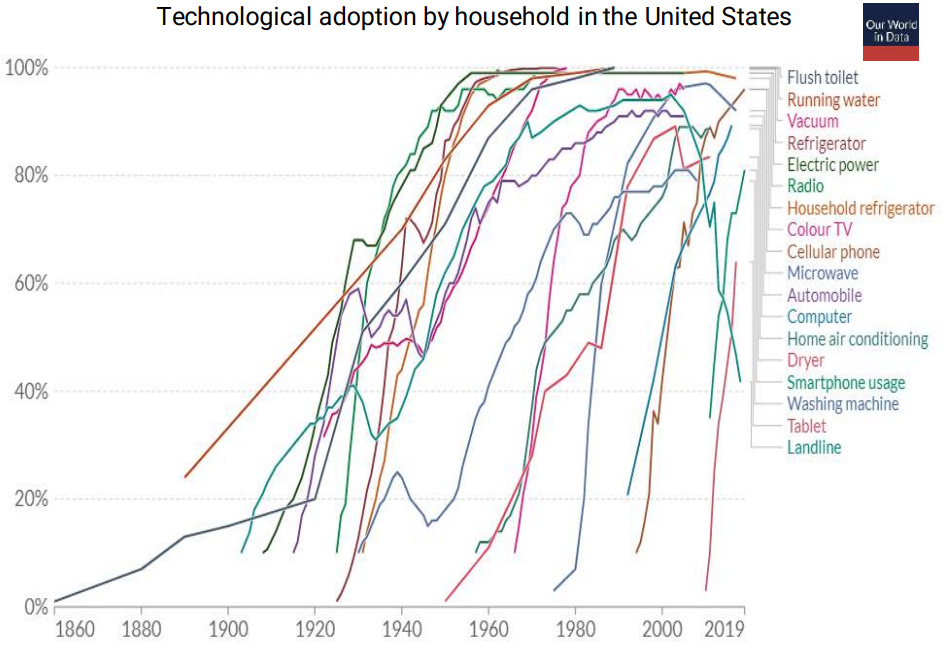

S-curves are graphs representing adoption of a technology in society over time and are reserved for very special technologies. The authors reference slides which show this graph which includes things like radio, phones, TV, refridgerators, toilets, running water, and electricity which all have followed this principle. They also show transportation from canals to railways, to roads, to airways have followed this principle as well. Things that currently may be following this principle are debated, but may include processing/computing power, artificial intelligence, metaverse, and cryptocurrency.

Here are some more examples referenced by the authors in other works. The authors argue renewables are already on their exponential rise and are in prime position for their S-curve of adoption similar to the likes of iron→steel, wind→steam engines, and horses→cars.

In each of these examples, the new technology was a stepwise improvement upon the predoscessor. It is undeniable that cars are better than horses 9/10 times, it’s better to make bridges out of steel than cast iron, radios are better than telegraphs, and toilets are better than, well, no toilets…

All of these technologies significantly improved the standard of living, reduced the effort/energy required achieve some end, and were in general a significant improvement compared to the last available technology. Is it truly a technological boom if its a struggle to achieve the same performance with renewables as what we already have with fossil fuels? Looking at things technologically is completely seperated from ascribing any morality onto the impact of fossil fuels.

The common counterpoint here is the “rails” (a technology is meaningless if the infastructure is not there). Cars are pointless without roads, trains without tracks, websites without the internet, and toilets without sewage networks. If wind/solar had all of the transmission infastrucure the picture would certainly be brighter. However, fossil fuels (not to mention nuclear) are inherently better technologies along the most basic metrics such as energy return on energy invested (EROEI), less material intensity, and higher capacity factors.

I don’t argue we shouldn’t use wind/solar/batteries at all, but to argue that they are better from a fundamental point of view even though they require intermittency mitigation strategies and are vastly less energy dense than fossil fuels or nuclear is silly. The main purpose of renewables is societal and environmental, not fundamental and technological.

Further, the authors argue in another piece that solar and wind are taking over coal/fossil fuels in the United States and Europe already and are beginning their widespread adoption phase which will usher fossil fuels obsolete technologically. As such, they claim it is renewables which are replacing coal for electricity generation. They point out that it was gas that fundamentally replaced coal for heating earlier in that article, but fail to point out that natural gas also significantly replaced coal for electricity during that same time period in that same article. Obviously it is a combination of both gas and renewables (actually mostly gas) which led to the reduction of coal, so the argument is uninformed or disingenuous to convince people of a prescribed narrative.

Another reason the authors pose is economies of scale which I’ve written about myself. I agree it’s as a reason for the tremendous cost cuts in renewables and batteries we have seen over the past decade, but also argue it is closer to terminous than them and pose it as a possible explanation as to why these cost cuts will not continue and accelerate as much as expected into the future. The authors assume that there is still a long way to go to reach economies of scale which will act as a tailwind for lower prices.

Time is another important factor to consider if it is assumed climate change is an existential threat. Biomass was the dominant energy source for hundreds of years. Coal was dominant for 60-70 years followed by oil/gas for about 50 years so far. Looking at total energy data for the world, alternative energy is a long way away from overtaking oil/gas even when including nuclear and hydropower. Articles praising the ability to decarbonize electricity are plentiful, overtaking total energy let alone fully decarbonizing by 2030 or even 2050 is a different story.

2. Lagging indicators

Look at new growth (mostly renewables), not current stock (mostly fossil fuels).

Most new energy brought online since 2019 is renewables and the share of EV sales is growing. Along with this point, the authors suggest peak fossil fuels is here and the IEA suggests it will be by 2030. This is a good point, renewables have definitely made the bulk of new additions in the US and if this were to continue then eventually they would overtake fossil fuels. One aspect is the pace of new additions and the other is that fossil fuel additions are down. First, in Wind Woes, I discuss how the offshore wind industry is facing troubles with higher costs and companies will have to raise prices to go through with a lot of projects. This can raise prices for consumers or the contracts get cancelled. Perhaps this is just a setback until interest rates and inflation subside. There was tremendous excitement about the space as well especially with new federal legislation and subsidies behind it. We will see if this pace can be kept up.

Another point is how oil companies are not investing in new production, but rather paying out dividends or share buybacks. Number of drilled but uncompleted wells in the US shows this phenomena, meaning companies are running through existing wells and not drilling new ones to replace them in recent years. There are many possible reasons for this behavior. Some ascribe it to greedy corporations trying to enrich executives, however the same people likely don’t want new oil production anyway. One of the other causes include volatility of oil prices leading to uncertainty about the profitibility going forward. Remember that oil futures went negative during covid and most new oil wells need a price greater than $50/barrel in the best locations just to breakeven. Factor in costs of production and any debt and still getting a decent return may be challenging even at current prices of $70-80/barrel. Further, a large company with cash like Exxon or Chevron can get paid risk free ~5% right now through US treasury bonds, giving a compelling alternative to drilling low margin oil wells.

Objectively, the current US political administration has sent mixed messages to the oil/gas industry through cancelling pipelines, being vocally against oil companies, low lease approvals, but also changing tune and asking for increased oil production later. Lastly, many shale oil wells were in prime locations and financed through debt and through the low interest rate environment that wind/solar enjoyed as well. These are some other factors why new oil wells have not been as common in the last few years.

While the current trend is your friend, I can see the case as to why it won’t be as smooth sailing along this front. Some firms like McKinsey have peak oil demand projections further out than the IEA or RMI. Oil could be stronger than expected post any recession, slower to go away, cost of capital can be problematic for new renewable projects, and political changes and stalemate in congress could mean subsidies to renewables slow.

3. Turning points

Peak in fossil fuel demand is here. With it comes increased disruption and accelerated change.

Once again this amounts to peak fossil fuel narratives. I laid out my thoughts above, but if peak oil demand is here, prices should trend lower over this decade.

4. Hardest to solve

Harder to solve sectors don’t hold back fossil fuel decline. Also innovation occurs in resourceful ways leading to an unpredictable and optomistic future.

Harder to solve issues like steel production, fertilizers, industrial heat, rubber, and plastics reliant on fossil fuels make up only 30% of demand. The point here is that all fossil fuels won’t be eliminated all at once and it will take longer to replace these more difficult industries. This also means that rapidly elimanting fossil fuels would mean that these vital industries would be at jeopardy which is a bad idea. I agree on this point overall, but whether artificial government intervention is justified to achieve an end, whether the 2030/2050 net zero timelines are realistic, and whether it can be done without nuclear energy is a completely different story.

I also agree on the second point about innovation. I’ve written about solid-state, sodium-ion, flow, metal air which can all be resourceful new technologies to replace demand for the stressed Li-ion sector for example. Sacrificing some energy density and using LFP instead of NMC cathode materials is another resourceful way to reduce material and cost impacts. In the entire calculus there will be some headwinds and some tailwinds. What is stronger is what prevails. Monetary debasement(inflation of natural resources) and artificially high demand from the government are very large headwinds to cost reductions from these technologies in my opinion.

5. Static world

The world isn’t static, it’s hard to imagine the future using today’s assumptions.

If it’s hard to assume the future, then why assume that solar cost will half again by 2030 like the authors do? This is ultimatly an extention of point 1, assuming renewables are a technological revolution. Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) is the common metric used to show the declining costs of renewables over time. This metric ignores grid and material impacts and has been argued to be flawed by other noteworthy writers Doomberg and GEM Energy Analytics. Even so, Bank of America has a new report that even this metric was too kind to renewables and has been revised less favorably.

6. Climate streetlight

Climate is not the only reason renewables will take over fossil fuels. Technology>commodities.

A lot of nice sounding words in this section, but they didn’t really say much new in my opinion. This section just says renewables are better and cheaper without any supporting data or sources and implies anyone skeptical is an ideologue not concerned with economics.

I think the market should decide what energy sources work for each area, but currently there are large subsidies for energy around the board. I obviously don’t know for certain, but it’s a tough sell that renewables are more economically viable than fossil fuels in a reasonable timeline without subsidy. There is disagreement on whether fossil fuel or renewables subsidies are higher, but the Congressional Budget Office reports more for renewables and this was in 2017 before the Infastructure and Inflation Reduction Acts.

While there are plenty of anti-climate and anti-renewable folks blinded by ideology trying to use Russia/Ukraine war to prove points or blind to China’s place as renewables leader, this seems more like a projection to me if anything. In my eyes, a good tell if someone is ideologically possessed (or uninformed) is whether they support nuclear energy.

The last point here is that renewables also rely heavily on a lot of commodities. Oil/gas is just replaced with steel, silicon, nickel, copper, lithium, and more. The authors claim that not switching to renewables is a threat to national security, but doing so would put us in direct reliance to the politically unfriendly China at least in the short-medium term. Energy and commodities are fundamental to everything and there is no escaping it.

7. Understating energy efficiency

Energy efficiency is just as important as switching to renewables.

We have gotten more efficient throughout the years. The authors admit this had little to do with renewables and it has done more for emissions reductions than renewables. They use this principle of human optimization as a reason why we will continue down to search for higher efficiency and this can often be found with renewables, heat pumps, and electric motors for example. I agree that these technologies can offer higher effeciencies in many instances. There are also tradeoffs based on geography, low capacity factor, low upfront efficiency, energy density limitations, etc. I think people/businesses are smart enough to make their own descisions based their circumstances in which option is right for them and that subsidies/bans are not optimal strategies. The market will play out what is best just as it has.

One of the comments on the post also makes a good point that much of the US energy efficiency was not “real.” The US has offshored manufacturing and its “real economy” of producing things to China and other countries willing to use coal and switched to a service sector economy based on finance and technology. The source supplied for this section use the economic output as a function of energy as evidence of improving energy efficiency, but the US economy today doesn’t have the same type of energy needs as 50 years ago or China today. The source also claims that failing to switch to renewables spreads nuclear weapons, terrorism, poverty, and military conflict. Their reasons were unclear which doesn’t help their credibility in my opinion.

8. Lost in complexity

Models of the future overestimate cost of renewables and are too complex.

The authors are likely talking about models like “the energy transistion will cost x trillion dollars which is unrealistic.” Again, this is of course possible and I’m sure their are many models that are extreme, but theres some good fundamental reasons not to be quite as optimistic about the technological change, economies of scale, and the overall economics as the authors are.

Further, if you want to keep things simple, EROEI is a more fundamental metric than the vastly more complex LCOE metrics most commonly used to highlight renewables.

My Thoughts

My main point is that it the insitant support for renewables is really about climate, not technology. That is completely fine. If you want to make an argument with moral judgements included for why renewables are better than fossil fuels that is another argument entirely and what makes it more ideological in nature. The authors even come back to that at the end in point 8. I disagree on the assumptions that wind/solar/batteries are technologically superior and will not face economic headwinds in an exponential rise to adoption where costs continue to fall.

If everything in that article turns out to be correct and we continue high standard of living with energy abundance through wind and solar, I would consider that a triumphant win and be happy to be wrong. I am clearly skeptical. Further, as anyone who has been a reader will know I am not against any form of energy, just merely like to point out potential pitfalls relying on mainstream views and present alternative ideas. I am fond of battery technology and even work in the field, but I am also bullish on nuclear energys part in providing energy and reducing emissions for example.

I’m not here to dunk on renewables. I’m here to deconvolute the information and be realistic about solutions. I don’t claim to know everything. What I do know about the future is it will not be one of magical renewable energy transition, but also not one of the current status quo.

We need nuclear, natual gas to displace coal, renewables, transportation networks, and a host of other technologies and methods going forward. The article presented makes some great points, but they are a bit misplaced and even a bit dishonest in my view. Next week I’ll share a list of my own “sins” that people don’t know/think about. Until then,

-Grayson

Leave a like and let me know what you think!

If you haven’t already, follow me at twitter @graysonhoteling and check out my latest post on notes.

Socials

Twitter/X - @graysonhoteling

LinkedIn - Grayson Hoteling

Archive - The Gray Area

Let someone know about The Gray Area and spread the word!

Great points!

I also think building huge battery backup systems for renewables, at least with lithium, is taking resources from the EV sector (and maybe driving prices higher?).