🔋Eight More Sins Of Analyzing The Energy Transition

There are more factors than just technology - why some analysts may be overestimating wind and solar in the energy transition.

Please support by leaving a like if you enjoy this article!

Last week I discussed an article that claims renewables (wind/solar) were technologically superior and as such people misunderstand and underestimate their potential adoption and price declines into the future. While the article makes some good points, their conclusions do not quite hit the mark for me. My takeaway is that renewables are about the climate, not truly technologically superior as the authors suggest. The idea that people underestimate technology does not completely apply here.

There are aspects of the energy transition that are less talked about. History and economics are both topics in addition to science that have insights we can use to predict the future. Here’s my list of eight “sins” if you will that people analyzing the energy transition miss.

History as a guide

Never before has the last form of primary energy consumption decreased substantially or has it been replaced by a less energy-dense form of energy. Now we are led to believe fossil fuels will become obsolete to renewables and this time is different. Coal replaced traditional biomass, but the amount used is similar to that of 1800. Oil/gas replaced coal, but coal consumption has not materially decreased. We can’t use history to predict the future, but it can be used as a guide. “History doesn’t repeat, but it does rhyme. Each change was a stepwise improvement in some capacity. It takes a lot to argue against over 200 years of energy transition history with a less energy-dense source of wind/solar.

As the global population grows and more people/countries are able to harness energy, the old forms have not gone away. This could change as the population stalls/decreases and/or enough of the world is wealthy enough to discontinue biomass and coal use. However, the world population peak is not for a while and more countries are being brought out of poverty with the help of all higher-level forms of energy. It is not fair to expect developing nations to adopt anything other than the most economical forms of energy, and if that’s fossil fuels then it will be harder to achieve a global energy transition with renewables.

Some countries and technologies moved quite fast. Individual countries, especially where it is politically possible to make large-scale changes can have exceptions. Individual actors around the world act in their own self-interest and not everyone agrees on the paths forward. France took 11 years to transform into a nuclear powerhouse and technologies like AC and fossil fuels were adopted extremely fast in certain countries.

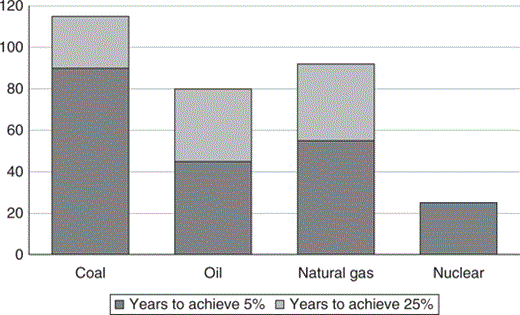

However, when talking about overall energy consumption, it takes a while. Coal took over 80 years to achieve 5% of energy consumption. Oil and natural gas took over 40. Then, it took 80-120 years just to reach 25% for both.

According to Our World In Data, wind/solar was just about 5% of total primary energy consumption by the end of 2022. Giving renewables the benefit of the doubt and choosing the turn of the century when wind/solar development began increasing meaningfully, it took 22 years to make it 5% (wind started to get added in 1989). This is about on par with how long nuclear took to grow to 5% from 1965 to 1987. This was about the point where Chernobyl occurred and the growth rate stalled out and eventually decreased so we don’t have any reference on the 25% mark for nuclear.

Given renewables have tied the nuclear energy record to 5%, we live in a more interconnected world with better transportation infrastructure now, and governments are seen as willing to dump money at the energy transition, it doesn’t hurt to be more optimistic. Coal took ~27 years and oil/gas took another ~37 years to reach 25% of energy. 10-20 years may be a reasonable estimate based on historical precedents and being optimistic. This is only 25% by 2033-2043. The world needs to be reliant on these technologies by 2050 according to mainstream climate change narratives. The historical timescale associated with energy transitions is an overlooked problem for a renewable energy revolution, especially since wind/solar would be the first transition to a less energy-dense source.

Renewables are dependent on fossil fuels

Renewables are primarily used for residential and commercial electricity generation. In the US, only 28% of the industrial sector and an insignificant share of the transportation sector energy comes from electricity. As we know, other countries with less stringent environmental regulations rely on coal for manufacturing and most of their industrial base. This is because electricity for industrial purposes is significantly more expensive than using fossil fuels. While these “hardest to solve” sectors only account for 30% of fossil fuel demand and may happen eventually through technology and optimization like renewable advocates suggest, they are required for the manufacturing of renewable technology as well as the mining sector for extracting raw material inputs. To say that renewables are dependent on fossil fuels is true, but also the path away from reliance is not clear on either 2030/2050 timelines for the whole world. Wealthy nations like the US may be able to pay their way to the desired outcome through large deficit spending, but the bulk of global manufacturing would likely remain elsewhere. Those wealthy countries would likely hypocritically continue to get goods from those locals as well. China permitted two coal plants per week in 2022 showing it is building out all forms of energy in addition to leading renewable and nuclear buildout.

Regardless of primary energy supply and even transportation, there is a plethora of petrochemicals and other necessities of current life derived from fossil fuels that have no viable commercial substitutes yet. Plastics, large transportation(jet fuel, diesel, etc), steel, tires, lubricants, carbons, fertilizers, mining equipment, industrial processes, etc. A lot of fossil fuels can go away but there will be demand for it for a long time, and wind/solar rely heavily on many of these industries to be built and function.

There is no energy transition without nuclear

While even nuclear cannot replace metallurgical coke, methane, or the host of other chemicals, it can do more than renewables. Not only can nuclear provide electricity much more consistently than fossil fuels or renewables, but it may compete for demand in industrial processes requiring heat which I mention in my review of advanced nuclear called SMR or SMH. Electricity plus heat is also a recipe most suitable for the production of clean hydrogen with electrolyzers if the hydrogen economy picks up. Other important processes that nuclear can help are desalination for more secure water supplies and large-scale transportation in ships for example. Renewables are reliant on fossil fuels, but nuclear can mitigate more of the harder-to-solve fossil fuel demand. This is all without mentioning the superior energy density and capacity factor nuclear energy offers. An energy transition absent nuclear is not a serious take.

Cheap energy

Energy is a base input into all economic activity whether it be manufacturing, electricity, agriculture, transportation, etc. As I mentioned above, manufacturing, mining, and to some extent shipping and construction are ways renewables will be dependent on fossil fuel inputs for a long time. Cheap fossil fuel energy is a major factor in the price declines of renewables. While economy of scale in growing technologies is the main reason, low energy input costs for their production are often overlooked. From 1998-2008 oil, gas, and coal were in steady uptrends in price. After the financial crisis in 2008, the trend reversed. Until the pandemic was over, we enjoyed low energy costs and had little worry about inflation. It is over this same time period that solar achieved its heroic price declines.

Low energy costs acted as a tailwind to this phenomenon, but this may not continue. Goehring & Rozencwajg and Lyn Alden are just two macro investors with research to suggest higher energy prices in the coming decade than what we’ve grown accustomed to. Take the below chart from Lyn which shows how the time spent above an arbitrarily “comfortable” oil price of ~$60 is what matters the most. The chart also does a good job of visualizing how oil prices may have felt cheap in recent years. Taking a look at oil with respect to gold instead of the increasingly debased dollar shows the point even clearer that energy has been cheap in recent memory.

The authors whose article I discussed last week argue that higher fossil fuel costs hurt the industry and lead to accelerated adoption of renewables. While it is true that high prices lead people to search for cheaper alternatives, this is not the end of this story. Higher energy costs make renewables more expensive or at the very least act as a headwind to the precipitous price declines many are expecting to continue this decade.

Finally, a rising price means that there is greater demand than is supplied by the market. For fossil fuels to become obsolete, you would like to see demand trend lower over time which would also be represented in the price going down. Oil prices are volatile and intertwined with economic growth, so lower demand due to recession does not really count as success on this metric. There may also be tighter supply in the medium-long term as companies have not been drilling new wells at the same pace.

Cheap capital

In the 1970s, inflation was a core theme which was eventually tamed through aggressive hawkish policy by the Federal Reserve in the 80s which saw the peak federal funds rate at ~18%. This means that that interest rates were arbitrarily raised by the US government which is generally shadowed by the rest of the world. The Federal Reserve began intervening in credit markets prior to the Great Depression by purchasing government securities (in effect lowering interest rates) and began formally controlling interest rates after World War II. Interest rates have been at record lows since the 2008 financial crisis and on a steady downtrend since the peak in the 1980s.

Before the Federal Reserve, it was up to individual lenders to determine the appropriate interest rate with the borrower. The current system is far from the free market at work. By manipulating interest rates lower, the Federal Reserve essentially subsidizes all investments, including energy. More oil/gas projects were funded leading to enough supply that the world was not concerned, which was a big factor for cheap energy.

Furthermore, low-cost loans meant that it was easier to get money through loans and the private debt markets. Renewable start-ups or other unprofitable ventures could tap essentially free money to operate their businesses. Interest rates have been heading higher recently and the guidance is that it will stay higher. While I suspect they will cut interest rates lower again, holding interest rates at near zero is akin to holding a balloon underwater, it’s only possible for so long. Again, most of the price declines in renewables occurred in an era of extremely low interest rates. Generally, this leads to all sorts of market distortions and malinvestment. This is another tailwind that has flipped into a headwind for all companies, including those involved in renewable energy projects.

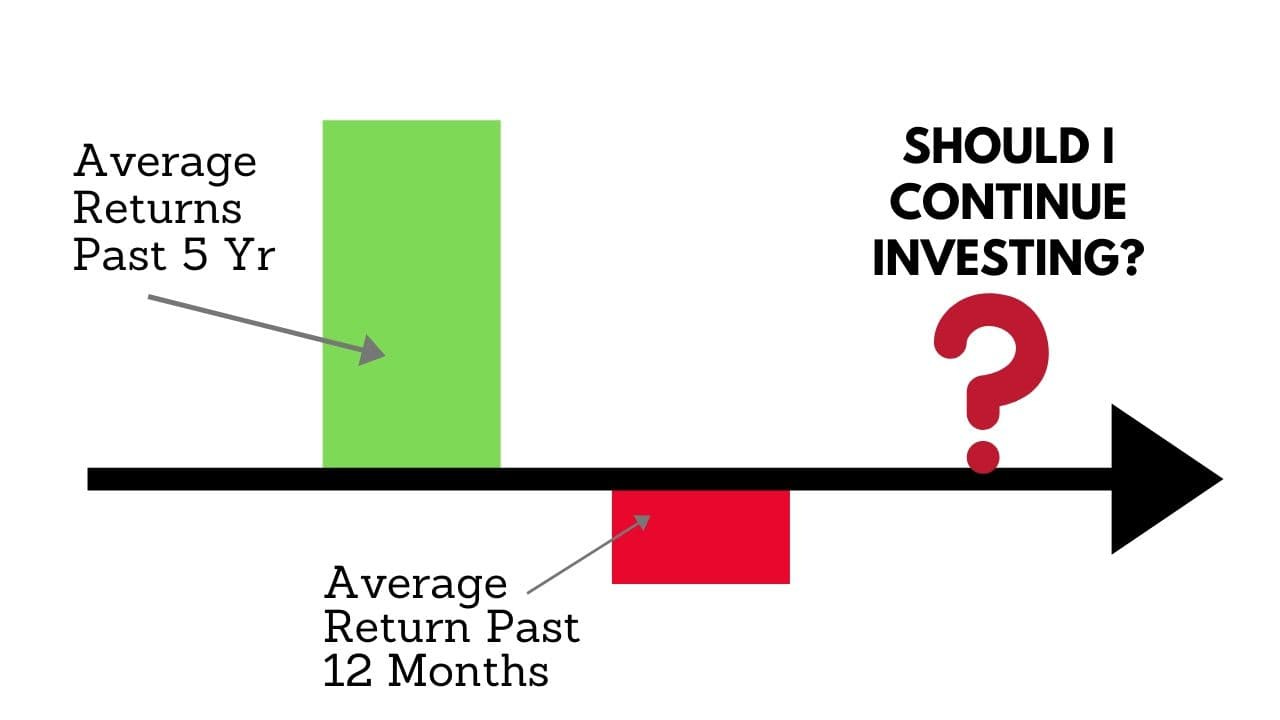

Recency bias

Recency bias is a natural psychological phenomenon where people extrapolate into the future what their lived experience has shown them thus far. This allows your brain to make assumptions so you don’t have to compute every possible outcome for everything all day long. You would probably be exhausted by noon if your brain didn’t do this, but it means we sometimes miss ulterior outcomes we haven’t seen yet. It can explain some of the classic investing mistakes for example. What is in recent memory can often blind the most realistic outcome, or the outcomes most probable based on statistics or fundamentals.

People point to recency bias to explain why renewable skeptics can’t accept the rapid changes forthcoming, but the same argument can be made in reverse. Yes, renewables may be a technological phenomenon poised to disrupt the fossil fuel era in our recency bias. It could also be recency bias to conclude the price declines seen since 2010 will inevitably continue considering many of the potential headwinds I’ve discussed.

“If we continue on existing learning and growth rates, then by 2030 the world will enjoy: sub $20/MWh solar, $30/MWh wind; $60/kWh Li-ion batteries and $1/kg green hydrogen (in optimal locations)” - RMI

Things are not continuing as they are though. Li-ion batteries and renewables have gone back up in cost and the stepwise declines in price declines are in the past. Wind developers are renegotiating contracts at higher prices and countries with higher penetration of renewables are associated with higher energy costs for consumers. Some of this is due to the more transitory aspects of inflation and interest rates raised aggressively by the Fed, but the big tailwinds of energy and interest rates will not be there as much going forward.

Money is important

Many of us have only lived in the “fiat-era” post-1971 where the government has limitless control to inflate the currency. This addicting tool’s ability to juice the economy and support whatever industries the government wants will slowly deteriorate over time as shown below. The debt burden from higher interest expenses also uses today’s money to pay for things from the past, causing a drag on economic growth. There are other tail risks like less demand for US bonds, which will be a burden on economic growth for the private sector and limit governments’ ability to borrow money. Ignoring any potential political constraints, more spending packages like the Inflation Reduction Act will have less value in the economy and contribute to inflation via new money creation as well.

Name the price

Anything can happen, but it depends on the price and the standard of living that it brings. Fossil fuels brought about lower prices, higher economic activity, new forms of transportation, more consumer goods, and more overall human prosperity at some expense to the environment. We may have the resources necessary to carry out a renewables-only energy transition, but at what price does it take companies to mine it out of the ground? How much government intervention would it take and what would the economic consequences be? What other environmental or geopolitical implications could this have? I’ve argued it’s at higher prices than now, partly due to demand dynamics in mining the metals, but also the issues with currency debasement.

We may be able to fly on “carbon-neutral” planes in the future, but if people have to pay more for the flight on their ticket or through inflation and flights can’t even go as far they won’t be happy. Each new era of innovation led to extraordinary improvements in the standard of living and way of life. Immense changes in infrastructure, transportation, and communication defined past eras. All a renewable age would represent would be a change in how we get the energy we are already accustomed to, some efficiency improvement with electricity generation, and some confidence that we mitigated human-caused emissions (although this could’ve been largely accomplished already and still possible through nuclear).

Conclusion

History, psychology, and economics all give important insights above and beyond merely the technical and environmental aspects of the energy transition. While governments around the world are trying their best to spur their picture of the energy transition, they more often get in their own way by blocking technology through subsidization, contributing to inflation and economic shocks, contributing to malinvestment via monetary intervention, and overreaching regulations with distrust of the free market.

The world has never regressed to lower energy-dense sources. Nuclear fits this bill as well as provides solutions to some things that wind and solar cannot. Cheap energy and capital have spurred investment into renewables which were massive tailwinds to their noteworthy price declines. Renewables are not inherently bad and they are wonderful technologies where they make the most sense. Is the next era defined by a wind and solar technology revolution yielding fossil fuels utterly obsolete though? I think there’s much the mainstream energy transition narrative is missing, so here are my eight sins of the energy transition.

-Grayson

Leave a like and let me know what you think!

If you haven’t already, follow me on Twitter/X @graysonhoteling and check out my latest post on notes.

Socials

Twitter/X - @graysonhoteling

LinkedIn - Grayson Hoteling

Archive - The Gray Area

Let someone know about The Gray Area and spread the word!